A mother waited anxiously outside a Texas elementary school. Her son didn’t walk out with the rest of his fifth-grade class.

“She panicked,” says Maricruz Martínez, a second-grade teacher in San Antonio. “She was so upset, asking: ‘Where is he? Who took him? Why is he not here?’ You could tell where her mind was going.”

Where did her son go? The child had simply stopped at the restroom.

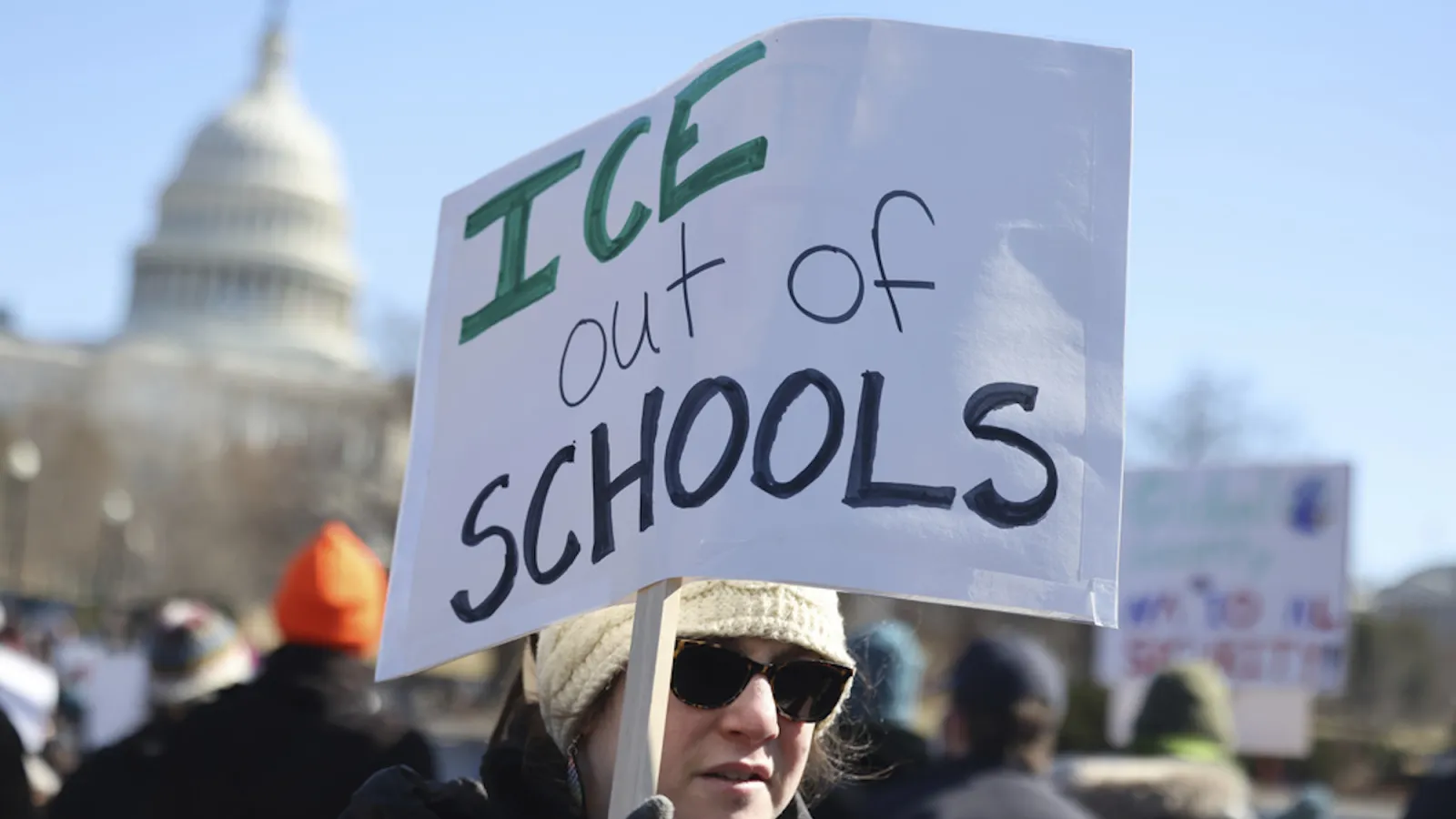

The danger is real. Many elected officials are creating a climate of fear, encouraging immigration raids, abductions, and deportations, and intentionally terrorizing families and communities. For those living through it, the absence of a child, even for a few minutes, can feel like a nightmare come true.

The raids are becoming more common across the country, and the mere rumor of a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) presence is enough to keep children home from school—and inflict academic and emotional harm.

The pain felt by children and families

Current immigration enforcement practices are causing significant stress, fear, uncertainty, anxiety, and even trauma for children, says Allison Bassett Ratto, a child clinical psychologist in Washington, D.C.

“What they see are their classmates, their family members, their neighbors often being apprehended in violent and confusing ways, while … doing things like picking up their children from the bus stop or going to their jobs,” she says. “This, for children, creates a sense that nowhere and no one is safe.”

She adds: “What is particularly worrisome to me as a child psychologist is that the stress, the anxiety, and the trauma … can become chronic, leading to both immediate and long-term damage to children’s mental and physical health.”

Underscoring this point is a July 2025 report from the University of California, Riverside, which confirms what many educators already know: “Even the threat of separation can generate profound emotional harm” for children of immigrant families, this can include anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems. Additionally, the constant fear that a parent or child might disappear can lead to school absenteeism, academic disengagement, and heightened emotional stress.

A classroom with a revolving door

A U.S. history teacher in Michigan, who teaches immigrant and refugee multilingual language learners from Central America, East Africa, and Afghanistan, sees the fear every day in his classroom.

“Some students stopped coming to school entirely or transferred to different schools in other parts of the country,” says William, who asked that his last name and school remain confidential to avoid drawing unwanted attention from ICE. “Other students’ [families] … decided to move back to their home countries because they didn’t feel particularly safe.”

One day, a student is present and engaged in class. The next, their seat is empty, with no explanation and many lingering questions.

“Our school has a lot of movement. People … join us throughout the school year, but also leave. With the Trump administration, it’s been scary,” William says. He acknowledges that when a student disappears from one day to the next, it’s “anxiety-inducing.”

When fear enters the classroom

The effect of immigration raids stretches into every corner of the classroom. Educators report plummeting attendance, emotional withdrawal, and families disappearing overnight—all of which has been driven by the Department of Homeland Security’s decision to rescind the “sensitive locations” memo, which once discouraged immigration raids in schools, churches, and hospitals.

Agustín Loredo, a longtime teacher and head soccer and cross-country coach in Baytown, Texas, recalls a student who told him quietly one day, “I live with my dad’s friend. I just put him down as an uncle.”

His father had been deported. His mother was in Honduras. The student was working full-time while trying to stay in school.

But toward the end of the 2024 – 2025 school year, the student stopped coming.

“It broke my heart, but I also understand. This kid has to eat,” Loredo says.

Quote byAgustín Loredo, a Mexican American studies high school teacher and coach in Bayton, Texas.

Not an isolated story

Following Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2025, reports poured into NEA from educators who witnessed the fallout directly in their classrooms.

An educator in Arizona reported that their school experienced a “near 50 percent absence rate one day because of a random rumor that ICE showed up to a local elementary school.”

A Michigan teacher shared how a seventh-grade student didn’t show up to school for three weeks. “His mother was scared to send him to school, since ICE is rounding up Indigenous people,” the teacher says. “He has only returned to school one or two days a week.”

Another educator in Pennsylvania noted: “One student is very anxious that her mother will be taken while she is at school. She is afraid she will go home, and no one will be there.”

Another reported terrified children clutching their passport cards in case they’re stopped and asked for their citizenship status. Kindergartners are asking, “Are they coming to take us away?” shared a Minnesota educator.

“I teach ESL students, almost all of whom are immigrants or refugees,” William says. “My students are afraid to come to school. Several have had parents deported. Many of my students don’t understand the hate and nativism that is being directed at them.”

The Weight of Uncertainty

To those outside immigrant communities, the fear may seem abstract. But to students and their families, it’s overwhelmingly real.

“Kids are coming to school with red eyes as they are home with overly stressed parents and all not getting enough sleep,” one Wisconsin educator shared with NEA.

Loredo, who teaches high school Spanish and Mexican American topics, underscores the hypocrisy in immigration attitudes: Welcoming immigrant labor while denying immigrant dignity, safety, and joy.

“It’s OK for them to work but not Ok for them to enjoy life here,” he says. “I think the problem is [industries] want cheap labor, and they want cheap labor that's scared.”

What you can do to help

Educators have responded by distributing red cards—wallet-size cards with language to assert one’s legal rights if approached by ICE agents. Many are taking “Know Your Rights” trainings to learn how to respond safely during encounters with ICE. Educators have also offered reassurances to immigrant families that they will continue to support them. Educators are most protected when actions like these occur off duty and not during the school day.

The district told us to stay out of it, Martínez says. “But we didn’t. We made sure to share the red cards with all of our members and families. … We’re here for them.”

Watch this video to learn how educators in L.A. are standing up for students and families.

Communities Team Up to Protect Students

Across the country, parents, educators, and community members are organizing and stepping up in record numbers to make sure immigrant families feel supported. Their goal is to strengthen communities through care, mutual aid, and advocacy. Here are some of the ways they work together to keep students safe:

Examples of community actions: